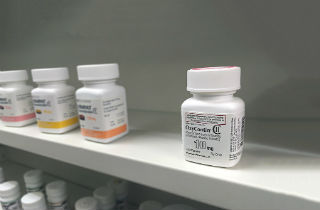

OxyContin reformulation: When, why…and does it stop addicts?

OxyContin – The perfect pain management drug?

The manufacturer of OxyContin, Purdue Pharma, originally marketed OxyContin as an appropriate treatment for chronic, moderate to severe, non-cancer pain. In the past, such strong opioids were used only for intractable, severe pain. So how did we end up with a national prescription pill problem and opiate addiction in rural areas? Following is a brief history of what has happened since OxyContin was introduced as a pain management drug in 1996.

Why OxyContin abuse skyrocketed

OxyContin’s release onto the market in 1996 coincided with a national movement to encourage doctors to treat pain more aggressively. The drug manufacturer of OxyContin, Purdue Pharma, originally thought the drug unattractive for addicts due to a time-release coating. But soon people found ways to crush the pills to snort or inject. These two events, added to the tendency of U.S. citizens to share prescription medications, gave perfect recipe for an opioid addiction disaster. At that time, few states had prescription monitoring programs, which also allowed the problem to grow and fester. Addicts could obtain opioid prescriptions from more than one doctor at a time, with no way for the doctor to detect the problem.

OxyContin was marketed aggressively to small town family doctors who didn’t have much experience treating chronic pain with powerful opioids. Few had the training to identify or treat addiction when it did develop. Rural areas had few places doctors could send patients who developed problems with opioid pain medications. By 2003, primary care doctors, with little or no experience or training in the treatment of long-term pain or addiction were prescribing about half of all the OxyContin prescriptions written in the country. (1)

Components of systemic opioid addiction

1. A national movement to encourage doctors to treat pain more aggressively

2. Addicts’ removal of time-release coating underestimated

3. Tendency of U.S. citizens to share prescription medications

4. Few prescription monitoring programs at the state level

5. Primary care doctors without pain management or addiction experience prescribe OxyContin

6. Misleading or false statements from the drug manufacturer

How Purdue Pharma misled the public about OxyContin

Purdue Pharma trained its sales representatives to make deceptive statements. Besides telling doctors that the drug was less likely to be abused, the sales representatives also gave false information about the risks of opioid withdrawal after stopping the pill. By 2003, the FDA had cited Purdue Pharma twice, for using misleading information in its promotional advertisements to doctors. (2)

OxyContin became such a commonly known drug to both abusers and the media that the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) asked for a report about the promotion of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma, information on factors affecting its abuse and diversion, and recommendations of how to curtail its misuse. This report, released in 2003, stated that by 2001, the sales of OxyContin were over 1 billion dollars per year, making it the most commonly prescribed brand of opioid medication for moderate to severe pain. (2)

In May of 2007, three officers of Purdue Pharma, a privately held company, pled guilty to misleading the public about the drug’s safety. Their chief executive officer, general counsel, and chief scientific officer pled guilty, as individuals, to misbranding a pharmaceutical. The executives did not serve jail time. Though they plead guilty, they claimed they personally had done nothing wrong, but accepted blame under the premise that an executive is responsible for the acts of the employees working under him. (3) The three executives’ fines totaled 34.5 million dollars, to be paid to Virginia, the state that brought the lawsuit.

Purdue Pharma agreed to pay a fine of $600 million. Though this is one of the largest amounts paid by a drug company for illegal marketing, Purdue made 2.8 billion dollars in sales revenue, from the time of its release in 1996 until 2001 alone.

Purdue Pharma has donated money towards helping communities treat opioid addiction, and has paid money as ordered by the court. Much of the $600 million award will go to states heavily afflicted by OxyContin addiction. This money will help to establish programs to help prevent and treat opioid addiction.

The reformulation of OxyContin – Is it harder for addicts to use?

At the congressional hearing in 2002, a Purdue Pharma representative said that the company was working on a re-formulation of OxyContin, to make it harder to use intravenously. This representative said they expected to have the re-formulated pill on the market within a few years. (4)

In 2010, this new preparation was finally released. It contains a substance that makes the pill turn into a gluey resin, difficult to snort or inject. Addicts don’t like the new OxyContin. They can’t inject this form of OxyContin, and it has a lower street value.

Is OxyContin good or evil?

Like most strong medications, OxyContin can be used correctly for pain management, or can be misused and cause harm to people and their families. Do you think OxyContin is bad or evil? Is it too addictive or caused too many social problems? And what about manufacturers of opioid medications? How liable should they be for the addictive effects of drugs? But is OxyContin the problem? And how can we all work to reduce the risk of addiction to prescription drugs?

Related Posts